NALANDA comes to VALOIS:

A response to His Holiness the Dalai Lama

It is so clear that His Holiness greatly appreciates Anthony “I really admire his spirit, his dedication for deeper human value.” But over the years His Holiness has brought out his view about Anthony’s view of synthesis. Most recently in October 2006, when he presented us a full size image of a tangka he commissioned:

HHDL: “Fundamentally he [Anthony] believed , all ancient Indian traditions must be same. He tried to (see) sameness.”

… “If Anthony were alive I would have told him that although all 17 of the masters were followers of one and the same teacher, the Buddha, there were differences: they had different interepretations of Buddhas teachings: you cannot synthesize them “

His Holiness says this with such good humor: and maybe to provoke us! Of course, for anyone who studied with Anthony, it seems far from Anthony’s view to ever want to mush all into one and say that “all ancient Indian traditions”, or even views, are same. Instead of 17 nalanda masters, imagine 12 sages from various traditions. Instead of Buddha at the center, place an image of reality, imagine each sage expressing and conveying some essential feature of Primordial Reality.

17 Nalanda Masters and Buddha

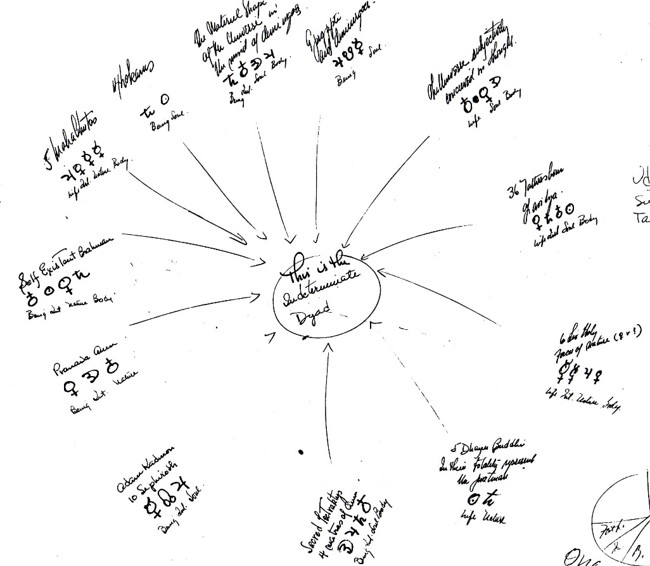

AD: 12 IDEAS and DYAD

Indeed, His Holiness statement that "although all 17 of the masters were followers of one and the same teacher, the Buddha, there were differences” could easily have been quoted from Anthony. Probably Anthony would also reverse it: although there were different views, they are not getting at different realities. For him there was no contradiction in sameness and difference. I believe His Holiness would appreciate these dimensions of Anthony's view of “juxtaposing philosophy”:

a. Unity does not exclude manyness. His Holiness, for example, speaks of the fundamental essence of all religions must be Kindness. Yet we see that this can encompass a multitude of expressions. Similarly, Anthony’s view that there was an ultimate reality did not preclude its expression in many traditions. The unity lies in the reality, not in the expression by different traditions.

In the tangka of 17 nalanda masters, although each master all has a viewpoint, they are also part of the same Mandala. This context indicates that in addition to being unique beings, they each are expressing the teachings of the same root master--: in this case the Buddha—or if we like, the Buddha nature. For Anthony also, each tradition had some essential perspectives on reality that were particularly well articulated. He felt that they fit together more like an orchestra: Each must be excellent in upholding its own sound: like the horn or cello. And all can be seen to form a symphony. As Rumi says: “when two Sufis meet they are one, and ten thousand.”

b. In the mandala, there is a central point which is both essence and common reality. Many spokes or rays indicate the many perspectives on or expressions of the central reality. The circle represents the wholeness or symphony and communion of the many views.

In his metaphysical mandala, Anthony tried to see, not how all were “one”, but exactly to maintain the uniqueness of various viewpoints, while indicating that they all were expressing reality, the common source of all. In the famous words of our lineage teacher Plotinus: “each is a unique form of the entire reality.” We distinguish in order to see the unity, the wholeness. “simplicity the other side of complexity” is the key. I believe something like this is what His Holiness means when he says he is a “simple Buddhist monk.”

c. For Anthony, as for His Holiness, these different perspectives deepened our understanding and appreciation of the philosophic question under investigation. As an example, I have heard His Holiness advise students who want a deep understanding of emptiness to study the early masters thoroughly: Chandrakirti, Buddhapalita, Bhavaviveka. Much of the development of the philosophic basis of Buddhism, unfolded by these great masters, happened in dialogue with the great non-buddhist sages of the time. All dialogue means some sameness and some difference. If there is no sameness at all, there is no basis of discussion. If there is only sameness, there is no point in the discussion. So: this is dialectic, weaving its way through the path of same and difference, motion and rest.

d. Anthony sought to use the dialectic between traditions exactly as His Holiness suggests in his Rimé approach: to deepen our comprehension of the question at hand. Anthony’s intent was not to merge the views, but to just get them to “talk:” to get them all in the same context where they could have a dialogue about their views. Not for the purpose of converting one to the other, but for the purpose of enhancing, widening and deepening their understanding and appreciation of the infinite reality. He did not suggest that such dialogue was a substitute for deeper contemplation: any more than studying the reasonings of several masters would preclude following a single practice deeply into realization.

e. There is some essential identity at the heart of all spiritual philosophy. This identity does not preclude myriad facets of expression. Each catches or expresses the light uniquely. His Holiness himself says many times: the essence of all religion is Kindness. This does not in any way reduce all to mush. But it does tells us an essential feature, in order to be a religion, kindness must be a dimension. Similarly, in order to be a philosophy, as Anthony thought of it, there must be some essential feature, something universally true. In his views of the One and Nous in Plotinus we see a paradigm for this relation of unity and multiple diamond facets of expression.

f. Reality being vast, all expressions are necessarily limited: every philosophy acknowledges that words cannot capture reality entire. They point, they help us see, but we don’t confuse them with the reality. Anthony wanted to show how the same word used by one tradition might mean something entirely opposite in another: or the opposite words might mean the same thing. No better example can be found than His Holiness’ own teaching on the union of old and new schools: where he points out that what Highest Yoga Tantra means by Clear Light is essentially the same as Rigpa or Primordial Awareness. Our tradition simply seeks to extend this “Rime” tradition past the boundaries of Tibetan Buddhism. For example, the Primorial Awareness (rig-pa or sems-nyid) of Dzog-chen cannot be other than the “Intrinsic Cognition” or Cit of the Advaita tradition: “capable of immediate use, but never an object.” We should not fail to point out the identity of meanings despite difference of words. Nor should we fail to make use of the rich variety of perspectives from different traditions in helping us to "fathom the unfathomable."

Looking into Mind Copyright 2019